by Paola Cesarini

“Yeşilçam” continues to move at a remarkably fast pace, packing a great deal of information in a short amount of time. International viewers are once again regaled with a crash course on Turkey’s post-WWII history, where external pressures from the Cold War and the Cyprus Crisis exacerbated existing class struggles and ideological conflicts. Amidst this complex historical backdrop and a cornucopia of erudite references, the intertwining tales of “Yeşilçam’s” main characters are becoming increasingly fascinating.

RECAP AND ANALYSIS

Episode 5 of “Yeşilçam” starts with Semih (Çağatay Ulusoy) illustrating to Turgut (Muhammet Kulu) his dangerous scheme to make two movies with Izzet Orkan’s money – albeit without the latter’s knowledge. The first narrates a love story in the context of a workers’ strike, while the second is the “nationalistic” film that Izzet (Özgür Çevik) commissioned. Semih, who employed the scheme before, wants to use it again to get back at Izzet’s arrogance.

.png)

In 1964, Semih’s film about a labor strike may as well have been ripped from the headlines. The Turkish Constitution recognized collective bargaining and striking as social rights only in 1961. It took, however, two more years for Parliament to enact the 1963 “Collective Bargaining, Strike and Lockout Law,” which implemented (albeit with various restrictions,) the labor rights proclaimed in the new constitution. The 1963 law was also the result of the successful mobilization of workers by emboldened trade unions. These events clearly inspired Turgut’s timely script.

Next, high dramedy takes place on the film set. Erhan Birsel, the handsome male lead (fabulously interpreted by Devrim Nas), is insecure, unreliable, and egomaniacal. He shows up to work drunk, refuses to sign a formal contract with Semih’s company, and complains incessantly that the film is beneath him. The petulant director Ertan Bayraktar laments that his coffee is never served according to his specifications. While Tülin (Afra Saraçoğlu) patiently rolls her eyes, Hakan (Bora Akkaş) is about to lose his mind. Semih eventually comes to the rescue. With his sharp negotiating skills in full display, he looks like a walker on a tightrope. Permanently at risk of losing his balance and crushing to death, he somehow manages to keep going.

.png)

Turgut meets with a fellow communist at a tea house, who warns him that Semih is just another capitalist entrepreneur interested in making money. He then urges Turgut to concentrate on the class struggle within the film industry, and not let personal considerations deviate him from this priority. As a former political prisoner, Turgut serves as the symbol of the Turkish state’s communist repression. While he remains a largely sympathetic character, this scene portrays communism as the shallow ideological counterpart to Izzet’s fascism. It remains to be said that, historically, extreme leftist ideologies never became as popular in Turkey as in most Southern European countries. Nevertheless, during the post-WWII Cold War era (and especially after Turkey’s 1952 accession to NATO,) anti-communism reached new heights. As a result, by the 1960s communism was largely confined to an elitist and intellectual segment of Turkish society.

Meanwhile, Reha (Yetkin Dikinciler) is having a meal with his family at a posh restaurant. His wife is a rich woman, who runs a pharmaceutical company. Together, they have a very spoiled daughter. Because Reha’s spouse provides the financial support for his production company, she feels entitled to humiliate him on a regular basis. It would thus appear that Reha is not always the powerful and sophisticated bully we have come to know. In his family context, the older producer is actually a frustrated misogynist, who is often emasculated by his powerful wife.

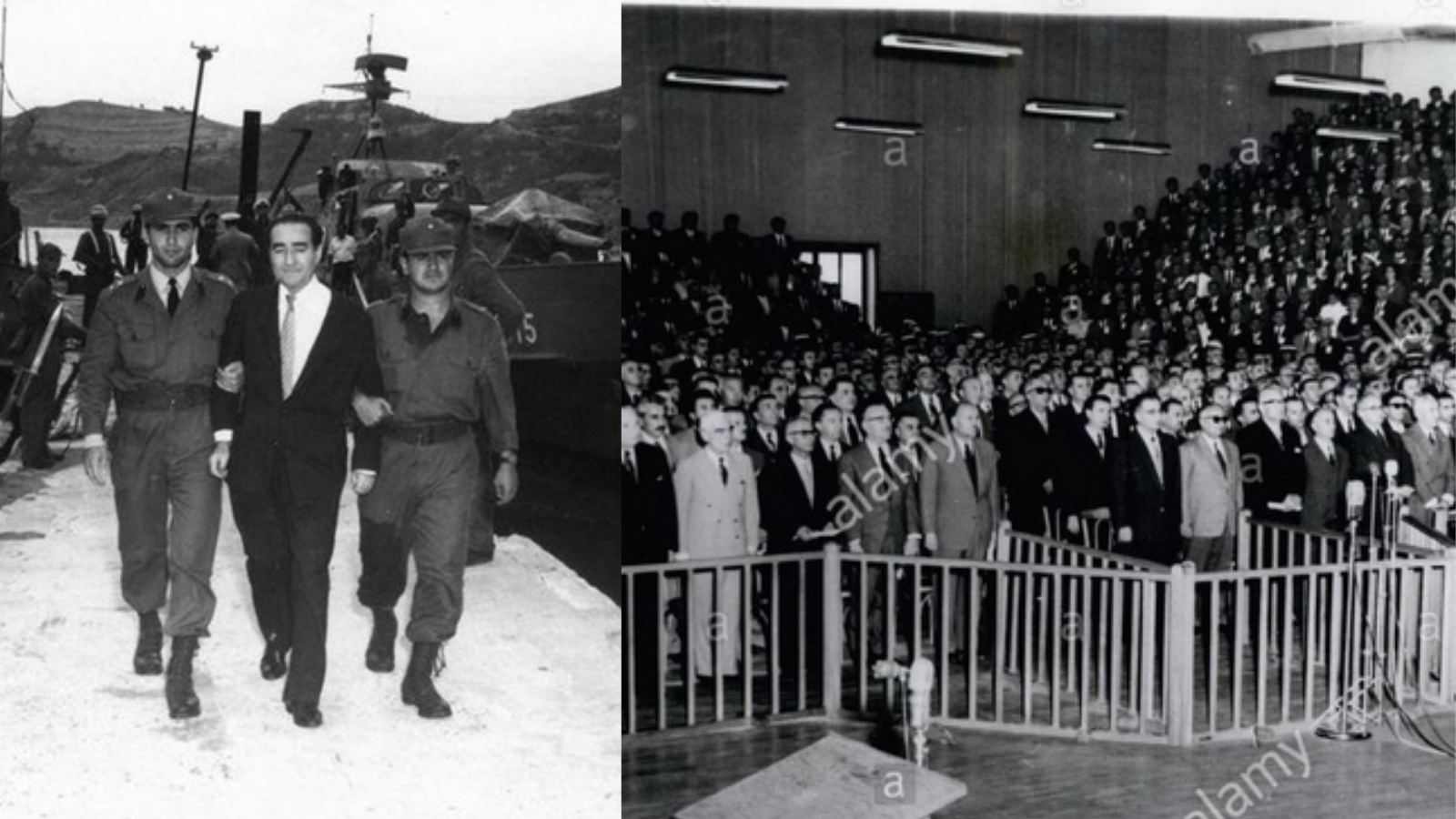

In the next scene, Reha meets with an investigator, who relates information on Belkis (Güngör Bayrak.) It turns out that the former courtesan is no longer as powerful as Reha thought, having lost much of her influence after the “27th of May.” Most international viewers may miss the reference to the 1960 coup d’état, which was ‘the first in a series of military interventions in politics that have continued to divide Turkish society.’ Faced with mounting political tension between the government and the opposition (led by the CHP,) a group of officers instigated a military takeover. Their stated objective was to prevent the ruling (DP) government from undermining the secular and progressive principles, which Atatürk had established for the new Turkish Republic. Later on, they created a “National Unity Committee” to preside over the drafting of a new constitution, conduct trials, and purges, and execute the democratically elected Prime Minister (Adnan Menderes) and two of his cabinet members on the Bosphorous island of Yassıada. When the first elections under the new constitution took place in 1961, the military returned the government to civilian rule.

Semih meets Izzet to hand him a first draft of the “nationalist” script. Izzet likes the plot and requests to meet the screenwriter. Faced with the impossibility of introducing a communist to the right-wing politician, Hakan offers his old schoolmate Bekir as Turgut’s replacement. After some intensive coaching, Bekir manages to impress Izzet with a few well-placed nationalistic platitudes. The scene clearly underscores the intellectual shallowness of the politician’s right-wing ideology. Later, Hakan recommends Bekir to Faik, who needs a well-endowed male actor to star in the porn film, which he is realizing for the two-faced Izzet.

Semih brings Erhan to the Monaliza club, in the apparent effort to soften the recalcitrant actor. There, they meet Vehbi (Onur Bilge,) Mine (Selin Şekerci) and Ayhan (Emre Taşkıran.) Mine’s open flirtation with Semih is interrupted by Tülin’s arrival, whom Erhan invited with the intent of seducing. Things, however, do not turn out well for the actor. With a clever subterfuge, Semih steals his signature on the contract and Tülin comically outs him as a sexist pig.

Armed with the information he received from the investigator, Reha visits Belkis to threaten her with nefarious consequences, should she reveal his relationship with Mine. The older woman looks a bit shaken by the unexpected confrontation. However, Reha is probably underestimating Belkis’ resourcefulness and will soon come to regret his bullying. Later, Reha and Mine have an intense argument over his visit to Belkis, and his heavy-handed attempts to control her.

With Erhan finally behaving, work on the film comes to completion, and a celebration ensues. Back at home, Semih is relaxing when Mine shows up. Their conversation reveals that their marriage ended because Semih is an obsessive workaholic (a creature of the cinema -- “Bir Yeşilçam Hayvan,”) and in time Mine got tired of the emotional rollercoaster, which his profession inflicted on their relationship. Their mutual attraction, however, lingers on and Mine spends the night with her ex-husband. Trouble between Semih and Reha clearly looms on the horizon.

Faik delivers his porn movie to Izzet, who recognizes Bekir from the leather bracelet. His reaction promises to be both ruthless and swift. As if this were not enough, poor Semih receives another unexpected (but this time wholly unwelcome) late-night visit from a mysterious man, called Rifki.

Episode 6 opens with a flashback to the 1955 anti-Greek riots in Istanbul (see episode 3-4 review.) We see a younger Semih walking amidst Turkish flags waving and protesters demanding military intervention in Cyprus. His reason for being out and about, however, is far from ideological. Indeed, he breaks into a house to steal the silverware. When Uncle Costa appears unexpectedly, Semih looks ashamed. But he is swift to react as a young man attacks Costa. After killing the aggressor, Semih proceeds to carry his injured mentor on his shoulders all the way to the nearest hospital.

These scenes contain at least three clever citations. First, in Virgil’s epic poem “Aeneid,” the hero carries his old father on his shoulders to save him from a burning Troy. The event symbolizes Aeneas’s determination not to leave his past behind, as he heads towards his predestined future. Perhaps the most important piece of ancient Roman literature, the “Aeneid” is an ode to duty and perseverance in the face of external challenges and our own failures, so that one day we may actually recover more than we lost.

.png)

In the most moving scene of the series thus far, Costa dies at the hospital with a desperate Semih at his side. With his last breath, he instructs the young man to use his money to make a film. In practice, Costa requests his “son” to make his dreams come true. He also absolves Semih for whatever sin he committed during the riots, assuring him that he will forever remain his “little friend.” Here, we find again the spirit of the “Aeneid,” and an explanation for Semih Ates’ film-making obsession. Since 1955, Semih’s driving purpose is to carry on Costa’s legacy. This sense of mission guides his actions to such extent, that he often sacrifices his own personal well-being to realize his mentor’s last wish.

The second reference is to the assassination of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink -- the editor-in-chief of the Turkish-Armenian newspaper Agos, who in 2007 was brutally shot by thugs driven by the same rabid ultra-nationalist ideology, which was responsible for the anti-Greek riots of 1955. Dink had received mounting threats after he urged Turkey to come to terms with its history and advocated for better ties between Turks and Armenians. The Turkish public reacted with shock to Dink's death. Over 100,000 people attended his funeral carrying signs that read: "We are all Armenians. We are all Hrant Dink." In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the Turkish government was partly to blame for Dink's death because it had failed to protect him. Now, fourteen years after his death, Director Çağan Irmak inserts an image from the assassination as a stark reminder of Dink’s sacrifice.

The third reference is to “Mandrake” -- the stage name that Costa gave to a young Semih when the latter performed magic tricks in a black top hat and white gloves, and which he utters again in his last wish (‘go tell Mandrake to make a movie.') Brought to life by Lee Falk in 1934, Mandrake is considered to be the first comics superhero. He is very popular in 1960s Turkey. As a matter of fact, it is Turkish director Oksal Pekmezoğlu who, in 1967, releases the unauthorized movie "Sihirbazlar Krali Mandrake Kiling'in Pesinde." To date, this remains the only theatrical film featuring Mandrake as the protagonist. While maintaining a public façade as a stage magician, Mandrake covertly fights criminals and supernatural entities using his superpowers. He is able to become invisible, shapeshift, levitate, and teleport. Most importantly, he can make people believe anything he wants, simply by gesturing hypnotically. Mandrake thus offers the perfect allegory for a filmmaker like Semih.

After Costa's death, Semih goes back to the house. There, he finds Rifki, who informs him that he disposed of the body and all the other evidence related to the murder. He describes himself as Semih’s “blood brother” and “his uncle’s son” and, consequently, demands that they share Costa’s money. (Given the broad use of these terms in the Turkish language, it remains unclear whether Rifki is actually Costa’s biological son.) Ten years later, the sinister Rifki is paying another visit to Semih. The producer confronts him but is interrupted by Mine’s appearance. Rifki subsequently departs with the promise to return. When Mine inquires about the mysterious man, Semih evades her questions. She is hurt and disappointed by his reticence and reminds him that such conduct contributed to their divorce.

Hakan is beaten up by a bunch of nationalist thugs and ends up in the hospital, where viewers are regaled with another comical interlude. Realizing that Izzet is behind Hakan’s beating, Aysel tries to warn him, but the politician’s arrival cuts their conversation short. Later that night, the poor girl suspiciously dies in a car accident.

In the meantime, Semih learns that the censorship board rejected his movie while, at the same time, Izzet (who probably had something to do with it) pressures him to start filming the nationalistic script. In the era of “Yeşilçam,” cinema and censorship often went hand in hand. The censors rejected Semih’s movie probably because -- like other films of the Social Realism Movement of the early 1960s -- it included ‘visuals or dialogues related to workers’ exploitation and oppression by wealthy bosses.' In the government's view, such images risked undermining the social order. The series effectively illustrates how producers like Semih tried to game the censorship. To begin with, ‘they would always work on two screenplays. The first version would be submitted to the censorship board, and the second version was the one to be shot. After the film was completed, the producers submitted an edited copy to the board and gave exhibitors the complete movie for public screening.' While the censorship board was formally removed in 1986, Turkish law continues to impose several limitations on TV and Film content.

Semih reaches out to Reha for help with the censorship board, but the latter makes his support contingent on Semih’s acceptance to work for him in Adana. Semih reluctantly consents. Next, we find Semih at Erol’s bar drowning his sorrow in alcohol, when Yilmaz drops by to congratulate him for the movie. He adds that the censors probably got offended because the film was too “real.’ He then invites Semih to have a drink together very soon. Who is Yilmaz, and will he be the one to come to Semih’s rescue?

When Reha informs Mine that he is sending Semih to Adana to keep him out of trouble (and of Mine’s sight,) she becomes distressed but manages to dissimulate her reaction. From their exchange, however, we learn that Reha was instrumental in advancing Mine’s career. We are thus left to wonder whether Semih's workaholic tendencies were only a pretext for their divorce.

Belkis drops by while Tülin is taking a lesson from Kuvvet. The disabled former prostitute, the young aspiring actress, and the transgender woman engage in a cheerful interaction that appears very progressive for 1964. Tülin is clearly fascinated by Beliks, even after learning that she used to be a high-society courtesan. Later, Belkis invites Tülin out for dinner and gives the young actress some pointed advice on how to survive in a world dominated by men. However, she also adds that – should she find the rare man, who seeks a lover that is his equal -- she should never let him go. For Tülin, that man is, of course, Semih. Consequently, she decides to go to his office to reveal her feelings, only to run away when she sees him kissing Mine.

Hakan comes out of the hospital and Mine takes him to her house to recuperate. There, thanks to Belkis’ subterfuge, Hakan becomes aware of his sister’s affair with Reha. They argue intensely and, after Hakan storms out, Mine goes to Semih’s office to end their budding reconciliation. She proclaims that their love is not enough and that she cannot handle another heartbreak. Semih is crestfallen since he had clearly been hoping that their love would get a second chance. Her words, however, are not far from the truth. What has always lacked between them is not love, but trust. Mine trusts Semih to become neither a better husband nor a more successful producer than in the past. She is also clearly afraid of Semih’s reaction, should he learn of her affair with Reha. And of Reha’s wrath, should he realize that she went back into Semih’s arms. Mine thus renounces once again to Semih’s love to ensure her survival.

CHARACTERS’ DEVELOPMENT

Semih: Last week, the Turkish press was overflowing with complimentary reviews of Çağatay Ulusoy’s performance in "Yeşilçam.” Indeed, Episodes 5 & 6 offer him a veritable smorgasbord in terms of acting. Early on, serious Semih gives way to angry Semih. We then meet diplomatic Semih, scheming Semih, annoyed Semih, sarcastic Semih, and aggressive Semih. Next, reflective Semih, nostalgic Semih, regretful Semih, traumatized Semih and scared Semih make their appearance. And last, but not least, we finally get to see romantic, passionate, and brokenhearted Semih.

However, it is devious Semih, who literally steals the show. Consequently, our favorite scene is that of episode 5, when the producer is listening in his office with British-like composure to the insufferably narcissistic Erhan blabber away about quitting the film. In reality, Semih is just lulling the actor into a false sense of comfort, while waiting for the perfect moment to strike. And strike he does when, with a burst of most evil laughter, Semih pulls out the contract with the actor’s signature and proceeds to give him his marching orders.

.png)

Episodes 5 & 6 of "Yeşilçam" reveal more about Semih’s past. The exchange with Turgut indicates that, while Semih claims to be a producer solely interested in telling stories, he is not as apolitical as he pretends to be. His reaction towards Izzet’s fascist ideology and the friendships he keeps with Turgut and Nebahat show – at a minimum – that Semih abhors rabid notions of nationalism based on ethnic or political discrimination. Moreover, Semih’s decision to produce a film about a strike reveals his support for workers’ rights. In the 1964 political climate, Semih’s movie is both timely and brave. Because it will inevitably irritate powerful people like Izzet, who still actively oppose workers’ rights in Turkey.

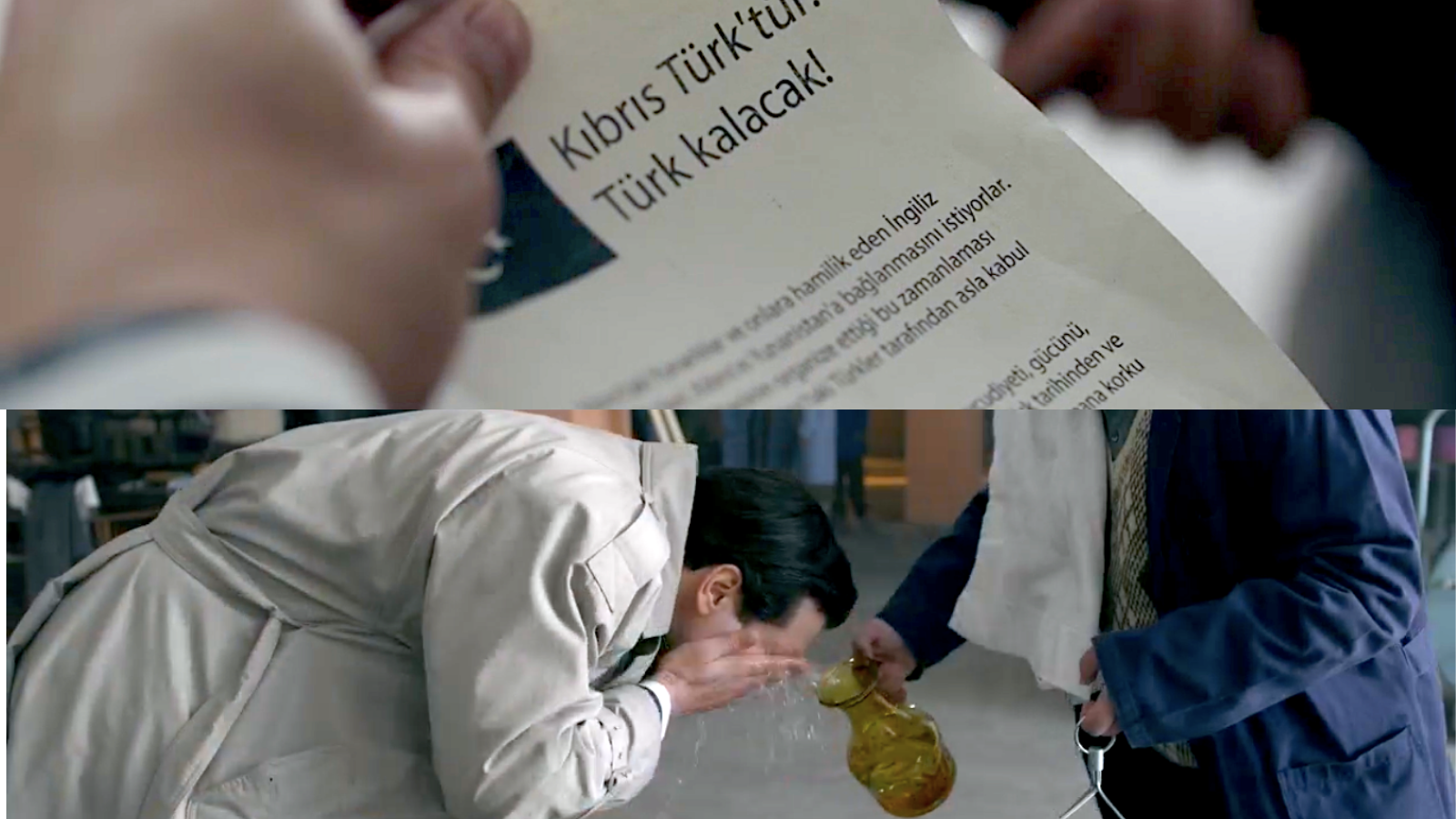

When Mümtaz shows him a propaganda leaflet about Cyprus and Rifki shows up at his doorstep, Semih experiences traumatic flashbacks. His reactions alternate between stress, shock, denial, and fear for his and his friends’ safety. As he experiences recurring visions of Uncle Costa, one thing is clear: the past is catching up to Semih. Clearly, he sees similarities between the "Cyprus Emergency" of 1955, which helped ignite the anti-Greeks riots of Istanbul (see eps. 3-4 review,) and the "Cyprus Crisis," which in 1964 was once again causing rabid nationalist sentiments to rise. In both instances, the intercommunal violence between Turks and Greeks on the island caused a surge of violence in the Turkish mainland against the minority communities still living in the country.

Turgut: The screenwriter fits well the communist intellectual archetype of the 1960-70s. Indeed, his character is probably modeled after the famous Turkish screenwriter, novelist, playwright, intellectual, teacher, and political activist Vedat Türkali. Known by international viewers as the author of “Fatmagül'ün Suçu Ne?” Türkali was often imprisoned during his lifetime for his controversial political writings and active involvement with the Communist Party.

Reha: He turns out to be both a misogynist and a control freak. He releases his frustrations by exercising perverse control over others, especially Mine. An ambiguous but ultimately dull character until recently, Reha is starting to exhibit a dark side. In so doing, Yetin Dikilnger reveals himself as the perfect choice for interpreting this cold-hearted and borderline paranoid character.

Mine: Her argument with Reha pushes Mine to seek solace in Semih’s arms. But what exactly is Mine’s game? "Yeşilçam" has yet satisfactorily to explain why such a proud and independent woman would choose to have an affair with the likes of Reha, especially while she still has feelings for Semih. Mine and Semih’s relationship defies understanding as well. While the series is progressively explaining the reasons behind their divorce, it remains to be seen whether there can be any real love left between two people, who continue to harbor secrets from each other. We shall have to wait and watch Mine’s reaction to Semih and Tülin’s growing attachment. And observe what she will do, once she discovers Reha’s efforts to undermine Semih. Selin Şekerci gets a chance to shine in episodes 5 & 6 of "Yeşilçam." As Mine, she flirts, seduces, dissimulates, gets angry, and lies while delivering a performance that results voluptuous and cunning at the same time.

Tülin: Afra Saraçoğlu’s comedy skills were on full display during her hilarious exchanges with Erhan. While her character has yet to be fully developed, Tülin is taking shape as Mine’s alter-ego. She is an idealist, while the older actress is pragmatic. Her star is ascending while Mine’s is declining. And contrary to Mine, she carefully avoids using her physical attributes to advance her career. Tülin is romantic but not naïve. She is very intelligent and can effectively stand up for herself when necessary. Her relationship with Semih has thus far been most professional. In episode 5, however, they have a “moment” on the film set, when he offers her a white rose to mark the completion of her first movie. A single white rose is generally regarded as a symbol of hope, respect, and devotion. It is a way of saying “I’m thinking of you.” If Semih and Tülin are destined for each other, it follows that viewers should expect to see more interaction between them in the upcoming episodes.

For the past three weeks, "Yeşilçam" has never ceased to surprise. Marketed originally as a light comedy set in the 1960s bright world of Turkish cinema, the BluTV series provides instead a serious opportunity of reflection on several dark chapters of recent Turkish history, which are seldom discussed because they remain controversial. When they chose to get involved in the "Yeşilçam" project, the producers, the screenwriters, the director, and the protagonists displayed both courage and civic virtue. Indeed, as the series' reference to the 2007 assassination of Hrant Dink reminds us, public figures in Turkey are still at risk whenever they bring up the topic of the country's treatment of minorities. In other societies with a difficult history -- such as Argentina, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, etc. -- TV series have made a critical contribution towards sparking a much-needed collective debate about the past. "Yeşilçam" will undoubtedly do the same for Turkey.

All sources for this article are included as hyperlinks. All pictures and video clips belong to their original owners, where applicable. No copyright infringement intended.

For more information about Çağatay Ulusoy visit the Cagatay Ulusoy International website and its various social media platforms.